Stages of Learning

In Part 1 of this blog, I set out an argument that not all stages of learning are the same and that these different stages have different characteristics. It is by understanding this and understanding the specific requirements placed on teachers at each stage that enables us to work with pupils in such a way that every single pupil is able to learn well and attain expertise in a subject.

I urge teachers and all involved in education to reject those assertions made about learning, based on examining just one single stage of learning, which attempt to portray teaching approaches as black and white, as good and bad. Most often, when we dig into all the bold claims being made as a retort against someone else’s bold claim, we find that each side has a point.

By stepping back and considering learning from a distance, we can see that it is a complex process; one that sees a pupil arrive novice and leave expert, through a long and necessary period of maturation.

In this part of the blog, I will discuss learning as a continuum of stages. The reader should not take the presentation of these stages to mean that they are distinct or indeed that they are linear – learning can be undone as readily as it can be built, so there is always likely to be a toing and froing between these stages. Also, the reader should not conclude that I am suggesting these stages as a full and final description of learning. I use these stages simply to give structure to the conversation.

We know a heck of a lot about learning. Approaching teaching armed with humanity’s cumulative knowledge about teaching means we can be forensic rather than random, we can be sustained rather than faddy, and we can be unswerving in our belief that all pupils can learn well. I think that’s no bad thing.

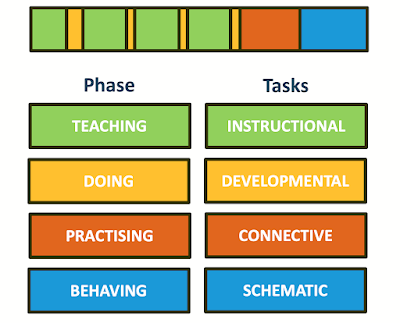

I think we can consider the stages in learning as being grouped into two broad phases, namely

1. Short-term knowledge acquisition phase

2. Durable knowledge growth phase

(Sidenote: I use the phrase short-term here deliberately, because I wish to highlight certain common aspects of classroom practice. But I am, of course, aware that I don’t really mean short-term; when knowledge is properly acquired, it doesn’t really leave us. It may well be out of reach and it may well seem long forgotten, but it is more often the case echoes remain, somewhere unknown and somewhere not yet understood. As a way of illustrating this point, try to think, for example, of a phone number or address or the layout of some streets from many years ago. They seem lost. But, if you were to be shown, let’s say, a list of four different phone numbers and asked to state which one of them was your childhood number, you will pretty much always get this correct. There’s an odd sensation when this happens – it feels rather good – and suddenly some other memories come back to life too. What is happening at this moment is a process of re-membering; your brain is creating a brand new memory associated to the fact at hand. This process of re-membering has a significant impact on the ability to recall later; the more times you recreate memories about a fact, the more readily you will be able to bring it to mind again.

For more discussion on cognitive architecture and memory, see my 2019 book, Teaching for Mastery.)

I present these two broad phases and the stages comprising them in a simple graphic, which I find helps in discussing the idea. I would not wish anyone to assume that this image is indicating a strict hierarchy, though, so please take with a huge pinch of salt.

These stages can be considered personal qualities that the pupil acquires as they make progress in learning. Each can be broken down further into stage-specific actions / dispositions / techniques as summarised below.

Awareness

· Readiness

· Story

· Metaphor

· Model

Inflexibility

· Exposition

· Example

Flexibility

· Non-example

· Boundaries

· Variation

· Principles

· Structures

Automaticity

· Replicate

· Rehearse

· Practise naively

Fluency

· Practise purposefully

· Practise deliberately

Connectivity

· Forward facing

· Transfer

· Method selection

Maturity

· Embed and behave

· Understand the Battleground

· Assimilate future learning

What follows is a brief description of how we might bring about those qualities. In Part 3 of this blog, I will consider each stage more fully, illustrating what these might look like in the classroom.

Bringing about Awareness

At the very moment of encountering an entirely new idea, all human beings rely on the same mechanism for successful learning; extending what we already know and believe to be true to make sense of a novel situation. We make sense of a new idea – literally being able to make new memories and new meaning – by translating the unknown into the known. We can accept new ideas if they make logical sense in the framework of what we already know and understand.

When describing a new concept to pupils, teachers must engage in a dialogue – we cannot simply pour new knowledge into the minds of pupils, we must negotiate the new meaning into existence in the pupil’s mind. Teachers use story to achieve this. They draw on metaphors, models and examples to weave together a story that pupils can make sense of because they have the underpinning grammar available to them that allows them to understand the narrative, they link the models and examples to ideas they already firmly understand, and they make logical, believable steps to convince themselves of the new truth.

This is only possible if the new idea can be translated into known ideas and this is only possible if the new idea is not too far beyond the pupil’s current understanding. We want pupils to grip every new idea they encounter; this starts with becoming aware of the idea in a meaningful way. This can only happen when the prerequisite ideas – the ideas that allow us to have the discussion about the new idea – are secure and brought to mind through story.

All of this is a rather longwinded way of saying that, before we embark on teaching a pupil a new idea, we must determine their readiness. There is no point in trying to teach anyone an idea so far beyond their concept of reality that they are bewildered and left feeling as though everything is being discussed in an alien language. If a pupil does not have a secure grip of the necessary prerequisite ideas, teachers should step back and address that issue before attempting to bring about new meaning.

Bringing about awareness of a new idea is a disruptive process – in a very real sense, we are asking an individual to change their view of the universe – but it need not be a difficult process, since we are able to bridge from the pupil’s current knowledge in small, logical leaps.

For more on bringing about awareness, see my 2020 blog, Models, Metaphors, Examples and Instruction.

Bringing about Inflexibility

When a pupil is aware of a new idea and it has begun to permeate their mind, sparking off connections to previously understood ideas, we can move further with the idea to a point where the pupil can gain a limited appreciation of how the new idea might be useful or might react or might inform or might be deployable. Teachers can achieve this further insight through exposition and example. We are not attempting here to bring about a durable understanding of an idea and all its implications, but merely setting out to give the pupil a foundation of success and comprehension that they may continue to build upon. Early success in gripping some of the applications or surprises or joy or power of a new idea can play a key role in creating conditions in which pupil ‘grit’ will sustain them through further study of the idea. These early steps in working with a new idea can be as simple as seeing that the new idea is a time-saving device for a simpler but long-winded approach with which the pupil is already familiar – recall, for example, learning a new formula in a spreadsheet and realising you no longer must do tedious data entry. That feels good, right? A teacher has told you how to use a formula, you can use it, it has benefit, it brings about a sense of pride and success and maybe sparks an interest in learning more about these types of approaches and maybe enables you to start that learning with a sense that, although you’re not quite sure why everything works, it will be something that will be worthwhile and will be surmountable.

Inflexible knowledge is limited. We are using new ideas in a restricted set of circumstances, and we are doing this deliberately. Attempting to appreciate the full range of meaning with a new idea is not a good strategy – we can all learn well, but only when we’re learning at the boundaries of our current understanding, which is not usually possible if we try to take in all the implications of a new idea at once.

The teacher can use exposition to carefully and explicitly, with detail and with specific examples, instruct the pupil. We tell them the facts; we tell them what to do.

I will pause here for a moment to put to bed any silly notion that inflexible knowledge is a synonym for ‘rote learning’. Rote learning is a term thrown around by those who wish to paint an entirely false picture of what teachers do. Rote learning is remembering facts in the absence of meaning. Almost no learning is rote. And it is vanishingly rare to see any teacher instructing without meaning. Using the slur of ‘rote learning’ as a way of discouraging teachers to take the crucial step of first establishing inflexible knowledge is simply an attempt to prevent all pupils from learning well. Inflexibility is knowing, remembering, and using facts with meaning but within deliberate constraints that enable pupils to experience early success and motivation.

When using examples to bring about inflexibility, teachers should vary the examples they use in their discussions and limit the number of problems pupils work on. We are in the short-term knowledge acquisition phase and the nature of practice is fundamentally different in this phase compared to the later durable knowledge growth phase.

Bringing about flexibility

Inflexible knowledge is a great motivation generator, but we would never wish to leave pupils limited. By examining examples and non-examples, teachers and pupils can iterate towards a set of circumstances when the new idea holds true and when it does not. Pupils can identify the boundaries of the new idea and have a much greater appreciation of when it is appropriate to apply the idea or not.

Bringing about flexibility means to bring about an understanding of how, when and why an idea is useful and appropriate. Teachers can guide pupils through carefully sequenced activities, deliberately varying the conditions such that pupils discern the underlying principles at play and get to view the mathematical structure supporting the idea and its applications.

Bringing about automaticity

Once a pupil is familiar with an idea, some of its applications and some of its limitations, we seek to empower the pupil by bringing about automaticity in working with the new idea. In other words, we set up activities and obstacles that they work through until they are able to perform without taking up great amounts of mental energy.

Teachers can work through detailed examples, applying the new idea in useful ways, narrating in detail the how and why of each step in the example, highlighting key moments and features and role-playing that sense of achievement when an apparently intractable problem is overcome. In return, pupils work on their own problem, replicating the steps the teacher has taken and paying careful attention to the key moments. This batting to and fro between example and problem, is a technique teachers use to ensure pupils have received the meaning they intended and can articulate the approach for themselves. When both teacher and pupil are confident they are singing from the same hymn sheet, the pupil can then engage in rehearsal; working with the new idea without the support of the teacher. This rehearsal does not require the pupil to work through endless questions, since here we are simply checking that meaning has been received rather than attempting to refine a pupil’s accuracy. At this stage, working on a small number of problems, but giving great attention to each, articulating to others (teacher or peer), and carefully unpacking the meaning of every step or decision, is far more important than simply getting through a list of questions.

Pupils can then progress to what we might call naïve practise, which sees the pupil working on problems with a general sense of what they wish to achieve and attaining a level of performance that is more or less automatic.

Recently, particularly in England but also in other Western systems, automaticity has become the goal of teaching and learning. This is a really bad goal. Automaticity is an important stage in learning, but hitting this plateau of performance means that pupils remain in their comfort zone and do not progress to expertise. Naïve practise resulting in automaticity is the kind of practice that most of us undertake in most areas of life; we achieve a point of ‘good enough’. We are in our comfort zone, don’t feel like a fool, are able to perform in most day-to-day situations and can feel good about what we are doing. For most of us, in most domains, ‘good enough’ is, well, good enough. But what we wish to achieve as the teacher is to reveal to pupils the awe and wonder of being expert. Ascending to elite performance necessarily requires us to operate at the limits of our comfort zone continually and not to be seduced by ‘good enough’.

Being at the limits of one’s comfort zone can be unpleasant – it can feel exhausting or frustrating or just damn right hard. To be able to persevere through difficulty requires ‘grit’.

All of us have some domain in which we willingly persevere in the face of difficulty (it is not yet known why this is the case, but there are some interesting studies indicating a genetic link to predisposition for perseverance in given circumstances). This ‘grit’ appears to be domain (subject) specific, which means schooling might be thought of as a race to discover the domain(s) in which a pupil will willingly persevere through tedium, pain, exclusion or sacrifice. It is vital that we do make this discovery for every single pupil or else their experience of schooling is one in which they never feel the wonder of expertise.

This puts an end to the stupid idea that there are pupils who can learn well and pupils who cannot. All pupils can. But they will have different levels of grit in different subject areas. Teachers already know this and have known this for a long time. We all know the pupil who is switched off in the mathematics classroom but on fire in the history classroom, for instance.

The trouble with the ‘grit’ debate is that it is sometimes used to excuse pupils from effort in those domains they do not have a proclivity towards. This is fair enough when we reach the highest levels of a domain, but for school level learning, it is possible to bring about in pupils a level of grit necessary to take their deftness with school level ideas to, or close to, expertise. We can think of this level of grit as ‘flow’.

Flow is a state of concentration, low self-awareness and enjoyment that typically occurs during activities that are challenging but matched in difficulty to the person’s level of understanding.

It is interesting to note that there is:

· Negative correlation between flow proneness and neuroticism

· Positive correlation between flow proneness and conscientiousness

· No correlation between flow proneness and intelligence.

Which is to say, flow proneness is associated with personality rather than intelligence. This is another nail in the coffin of the entirely wrong notion that only intelligent people can apply themselves with determination. It is important to keep banging this drum; all pupils can learn well.

I will cover the concepts of ‘grit’ and ‘flow’ in depth later, but for now it is useful to consider ‘flow’ as a state of effortless attention that relies on different mechanisms from those involved in attention during mental effort.

With forensic teaching and an appropriate level of pupil grit, the ascent to expertise can continue for all.

Bringing about Fluency

Fluency is a state in which a pupil no longer finds it necessary to attend in order to perform with skill.

This state has a key difference to automaticity, when the pupil could perform without the need for great attention and understood what they were doing. That difference is skill.

‘Skill’ can be summarised as ‘reliably replicable knowledge’. The emphasis here is on the ‘reliably’. So far, the type of practice that the pupil has engaged with has been aimed at attaining an effortless ability to do. By understanding the idea, knowing about its underlying principles and its boundaries, knowing when it is appropriate to apply the idea, and having rehearsed the idea to a level of comfortable familiarity, the pupil is able to articulate their understanding and solve problems using well embedded procedures. But, like all of us who have practised anything to the point of ‘good enough’, the pupil will regularly make errors – these are genuine slip ups, not an indication of a lack of understanding, but just natural inaccuracies in following an algorithm, procedure or approach.

Our ambition now for the pupil is for them to become skilled at working with the idea. This means they will be able to replicate an appropriate application of the idea reliably – their performance becomes elite rather than just good enough.

Naïve practise will not achieve this. The pupil must be made aware of their level of accuracy and the micro ideas or steps contributing to working with an idea that are cropping up as natural errors from time to time. This could be through feedback from the teacher or a whole host of instant feedback methods (such as being shown worked solutions or having a digital programme monitor steps and pinpoint advice). The critical point is that the feedback is timely – that the feedback happens in real time.

Armed with the knowledge of the slips they are making, pupils can now engage in a more powerful form of practise, which is most often referred to as ‘purposeful practise’. Purposeful practise, as the name suggests, has a purpose; the pupil has an aim to improve their accuracy.

How accurate should the pupil become? How much practice is required?

The answer to these questions will vary depending on the importance of the idea and how much future learning rests upon it.

Suppose a pupil wishes to secure their knowledge of multiplication facts through to 10x10. Are you ok with them getting one in every 10 questions incorrect? One in every 30? Or 50? Or 100? What if, instead, it was a heart surgeon performing an operation? What level of accuracy might you be comfortable with then?

These incremental improvements in accuracy for the pupil act as targets. The pupil who is making one mistake in 10 problems can be given the target to reduce their error rate to one in 20, say. And so on. The pupil can work with purpose because they have immediate feedback and a concrete goal to achieve.

Purposeful practise can significantly improve a pupil’s accuracy and take them much closer to true fluency, but to really nail this stage and acquire the quality of fluency, we have a final tool at our disposal; deliberate practise.

Deliberate practise brings into play the most powerful weapon a pupil has in their fight to learn more and more and more: the expert teacher.

Rather than the pupil simply working hard to improve their accuracy based on the binary feedback of correct or incorrect, telling them what to improve, deliberate practise includes specific, targeted advice from their teacher or coach on how to improve.

Suppose, for example, a pupil has recently been introduced to the idea of multiplication over a bracket and is well rehearsed at writing expressions such as 2(x+5) in their expanded form but is making the (very common) error of occasionally forgetting to multiply the second term and instead taking their cue from the operator, so they are writing solutions such as 2(x+5) = 2x+7 or 4(3x-6) = 12x-2 every now and then. They have worked doggedly to reduce their error rate and now only make this slip every one in 100 times. It is not the case that they don’t know what they are doing, but still these little errors are creeping in.

At the deliberate practise step, their teacher speaks to them about the errors they are making and, because we have been teaching mathematics for millennia and know a huge amount about how to overcome common misconceptions, the teacher then instructs the pupil in a method that is known to address this very specific issue (in this case, for example, when pupils are missing the need to multiply the second term, we can show the pupil an alternative format for presenting the problem, such as a grid or area, which really hammers home the need to multiply). Now the pupil can advance further and improve their performance to elite standard.

Having elite performance in every little micro-skill of mathematics means that, when these skills inevitably appear in future areas of mathematics, the pupil is free to concentrate on the new idea and has no demand on their mental energy when dealing with the component micro-skills. This is what I was referring to earlier when I described pupils having the mathematical grammar that allows them to have a meaningful discussion about a new idea.

(Side note: Deliberate practise is what is most often being described when people talk about ‘coaching’. In schooling, it is the expert subject teacher who acts as the coach. Coaching is only possible in domains where there exist agreed standards of excellence. This is why it is a myth that we can coach people how to be a teacher – since teaching, and education as a whole, is a domain with no shared standards of excellence, which I find deeply saddening and hope that, one day, the ideological bickering will end, and we can iterate together towards such a set of standards.)

Bringing about connectivity

As mentioned earlier, the stages I am describing are not linear. Connectivity could and should be a focus throughout. I place it here in the story simply because it is when pupils have achieved a level of fluency that connectivity becomes truly exciting and joyful.

Mathematics, in common with most subjects, is not a dull march through a tick-list of marketable skills that happen to stack up in a precise order. Mathematics is far better conceptualised as interconnected webs of ideas. The individual ideas and the webs they form interact with all others. As the pupil learns more and more ideas, they are able to see the bigger picture or the stories the webs tell and the more and more of these webs that are weaved, the more vantage points they have to look at old ideas afresh and build new mathematical understanding.

Teachers can help pave the way to connectivity by ensuring the methods and approaches they introduce pupils to are ‘forward-facing’, which is to say that they continue to hold true as the subject evolves and new ideas build on old. Taking a forward-facing approach helps to weave into existence a narrative that links prior learning to current learning to future learning. It helps to demystify mathematics and make it easier for pupils to grip new ideas without the unnecessary step of undoing previously held misconceptions.

Additionally, taking a forward-facing approach to teaching mathematics significantly increases the moments of wonder and joy that pupils will experience throughout their time at school and beyond – those beautiful moments when a light goes on above a pupil’s head and they exclaim, ‘ah, so that’s why we learnt that thing years ago!’ Imagine, for example, the pupil who has experienced a forward-facing education being able to follow the thread from learning about casting shadows in pre-school, through reflections and rotations in primary, vectors and matrices in secondary and culminating with the revelation of eigenvectors and values and all their wondrous uses as they pull it all together during a mathematics degree and realise their mathematics education was a continuum and a story.

Connectivity in learning mathematics unlocks the power of transfer; when pupils are able to draw on ideas they have learnt about in the past and use them like tools in their mathematical repertoire to attack unfamiliar problems in entirely different circumstances to when they first encountered the ideas, combining many different ideas in applications of mathematics so varied and interesting that they are able to begin to behave as mathematicians behave, knowing when and why to select particular methods and how to adapt them to meet new demands.

Bringing about maturation

Time. Really, it’s about time.

As pupils learn mathematics, over many years, webs of ideas form and the connections between them strengthen. Pupils can shine entirely new light on old ideas and can see how mathematics is not static.

This final step in becoming expert is all about pupils having ample opportunity to behave mathematically in genuine and sincere ways, working on meaningful problems and properly having the chance to see mathematics as a way of thinking, a way of being.

It is through these opportunities that pupils are able see mathematics as a living and breathing subject, one with a history and a future, one where every single idea that it contains is merely a point on a journey. Mathematics is a great truth making machine, it iterates and improves. The subject is a battleground.

Every idea that is currently accepted in mathematics marks the point at which one idea was defeated by a new, more powerful idea. Mathematics has a history, it is moving and continuous, which means schools seeking to give pupils the mechanisms for bringing about the best which will be thought and said in the future, must present mathematics as histories.

To become educated means to become aware of the origins and growth of knowledge and knowledge systems; to be familiar with the intellectual and creative processes by which the best which has been thought and said has been produced; to learn how to participate in what Robert Maynard Hutchins once called ‘The Great Conversation’.

Behaving mathematically is the main focus of my next book, so I will leave further discussion of maturation until then.

Phases of learning

Some readers might recognise the discussion above as an alternative articulation of my ‘Teach, Do, Practise, Behave’ model of learning (see my 2019 Teaching for Mastery book).

As the TDPB model evolves in my head, I am keen to describe its structure further. The brief descriptions of the stages above are hopefully a quick insight into that structure. In the next part of this blog, I will take each of the stages and describe them more fully, with a particular emphasis on how this might practically be applied in the classroom in a coherent approach to teaching and learning.

A coherent approach to teaching and learning can significantly increase the chances of every single pupil successfully gripping mathematics, but we have allowed actors in the education space to promulgate the notion that we do not know the most effective ways of teaching and that learning is some mystical, unknowable quiddity. This narrative is used to justify continual experimentation and fads. There is perhaps no more damaging an idea in education than the idea that we have no idea about education. We know lots about how to educate and what it means to be an educated person. We should not shy away from that knowledge, which has been so hard won by generations of educators before us. Let’s not deny any pupil the benefits of that knowledge.